This month the Queer Etsy Team is presenting our personal tales from school to offer hope for LGBT students returning to school with trepidation. May they learn from us that there is always someone out there who understands and supports them... Today's story is written by Mariana Romo-Carmona and was originally published in Queer 13: Lesbian And Gay Writers Recall Seventh Grade. Mariana creates & sells beautiful Chilean-style jewelry at Livingatnight on Etsy and you can read more about it at her blog, Livingatnight Chilean Arts.

Photo by Derek Visser

On some suburban street in central Connecticut, there must be a pink dogwood tree that is fully grown by now and opens every spring in beautiful blossoms of an inexpressibly, superbly pink, pink. I know this because in the spring of 1967 I walked to school every day and passed that tree. It had been a long, very snowy winter, and the little tree saved my soul when it bloomed.

At the very early hour of seven thirty, I passed that tree on the way to Alfred Plant Jr. High School. I usually walked alone because I was the new South American girl at school and I didn’t have many friends. In fact, I didn’t have any. The neatly trimmed lawns with sprouting crocuses and daffodils became familiar. The faux-Tudor facades and the brick and white clapboard houses with wraparound wooden porches and flower boxes all became part of what I learned to understand was suburban in that pretentious neighborhood. My own home was the middle floor apartment of a three-story wooden house on the main road, painted gray like its duplicate neighbors. I came to know that this is where the working class and the immigrant class lived, not in the smaller streets with the manicured gardens and nasturtiums by the hedge. Having no one to muse to about these things except myself, I did plenty of musing. Besides, after seven months my English was still somewhat flat and rudimentary. I couldn’t explain the finer points of the opinions I was forming. At least, the weather was improving and I was feeling a little less depressed.

My tree helped. It became my tree. It was not much taller than I was then, about five feet, and its dark brown branches bent in such poetic fashion-- small palms upturned, small hands dancing, I would sometimes sigh when I saw it. The blossoms opened and blushed so exquisitely that I would stop and gaze at the delicate arrangement with half-closed lids until I had drunk in all the tree’s beauty. My heart felt soothed after glimpsing my tree and I would march on to school where I would be the foreign girl again and nothing more for the rest of the day.

Once, though, one of the more tolerant girls in my class happened to be leaving her yellow and rust Victorianish house when I passed by and she didn’t make an excuse, such as having to get to home room early, so she walked to school with me. Her name was Andrea; she had curly brown hair and glasses. She could almost look like me, except she didn’t; she was clearly American and she kept to her tall, slightly goofy stride and nerdy New England patter. When we passed my tree, in a rush of budding adolescence and South American romanticism, I decided to confide in her.

“Look,” I said, gesturing poetically. “There is the tree I love.”

“Excuse me?”

“Oh, are you all right?” I asked, concerned that she may have hurt herself, or burped, and asked to be excused.

“No, I mean, what tree?” She shoved her horn rim glasses back up on the bridge of her nose.

“The small tree with the pink blossoms. It is so lovely, I am in love with this tree!”

“Oh.” Andrea looked around to make sure we had not been seen together. We hadn’t, so she quizzed me again. “What do you mean you are in love with the tree?”

“I love this tree because its beauty... upsets my heart so!” I explained, transported.

“Well, you can like a tree, that I can understand,” she said, as she resumed her pace up the street. “But you can’t be in love with it, that’s all!”

I don’t think that Andrea talked to me very much after that day. She was in practically all my classes, but whenever I saw her she adopted a kind yet pained expression and excused herself, as though she were a missionary and I an exuberant savage who might cause a scene with my unruly passions.

I got used to this way for things to be, for the rest of my high school years and into college. There was no way that I wasn’t going to be a little bit odd, wherever I was, and I realized years later that being an immigrant, usually the only Latina in any situation, was only part of the reason. I am sure that the episode with the pink dogwood expressed feelings that had already been stirring in my heart.

Photo from peregrine blue on flickr

Before we emigrated to the United States, my parents had gone to the north of Chile in search of better jobs. We left Santiago with its old streets and comfortable familiarity and moved to Calama, a small oasis town in the middle of the Atacama Desert. Everything was new there, the houses, the schools, the theater, and even the buses, which were clean and speedy without the spewing of ugly diesel we had to smell in the capital. The sky in Calama was always blue; it never rained, and some of its relative well-being seemed to have spilled over from the only nearby town, the copper mining Chuquicamata.

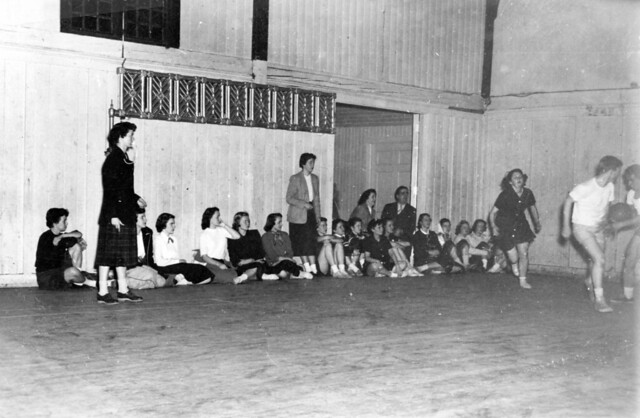

In Calama, I was enrolled in the only girls school, which was the norm in Chile. This one happened to be a Catholic one, run by Spanish nuns of the Dominican Order. There was a co-ed public school, but when my very progressive parents had to choose between a secular education and one where I would be safe from adolescent boys, there was no question. And I certainly didn’t mind.

The code of behavior at the school was the same as in all girls’ schools, I imagine. That is how I had grown up, with women teachers and surrounded by girls like myself. So my new school provided me with something familiar, the same comfort that all Chilean girls had experienced before me, as had my mother and all her sisters. I wonder now how much of this is lost with the introduction of co-ed schools as a rule.

But the important development at this new school was that we were all entering the years of existential angst, of longing for the unfathomable reaches of love. We were sort of programmed to make our parents’ lives miserable. At least at school we had each other, we were very democratically in love with each other and sexual orientation had little to do with this. Even though our devotion was unshakeable, we were growing up in the 1960's and most of us did imagine ourselves as starlets in Hollywood movies who would one day date one of the Beatles, preferably Paul.

I remember the day of my initiation. It was recess and I’d gone to stand by two girls sitting together on the sunniest part of the steps by the playground. This was the desert, but winter mornings were cool. Fatima was a beautiful girl with long black hair and shaded eyes from her luxurious eyelashes. I don’t think there was one of us who didn’t long to be her best friend. Next to her on the steps was María Eugenia who was the favorite of the nuns for being an orphan, or at least half an orphan because only her father was dead, and because she stayed in the school all the weekends, including holidays. As for me, I had nothing to recommend me; I was an ordinary Chilean girl.

Fatima and María Eugenia were playing at hiding María Eugenia’s gold chain within the folds of her shirt collar. Fatima had to find it with her fingers before her friend raised her shoulders and hid her neck in the collar of the uniform’s white shirt and navy blue sweater. Fatima’s fingers couldn’t reach far enough. They invited me to join them. María Eugenia winked at me with playful brown eyes, her lips in a teenage smirk all defiance and beckoning.

I sat with them on the steps, all three of us in navy blue pleated skirts, our legs gathered underneath sporting cinnamon colored knee socks, and of course, brown leather shoes with a spit shine. We played the game and soon gathered a crowd around us, the desert sky shining blue above. There was a lot of shoving and laughing, and within five minutes it seemed I had known those uniformed girls all my life. María Eugenia pulled up her chain and told me to try and get it-- it was a stupid game, I know, but how delicious.

It didn’t take long. I guess Fatima was tired of the game, so she let me try, draping her arm around me, instructing me on how to grab the chain before María Eugenia shrugged her shoulders and it slipped away. I placed my hands on María Eugenia’s shoulders and waited for her to let go of the chain. She was clearly enjoying the attention. “Ready?” she asked me, and dropped the chain down her neck and into the folds of her shirt. I dipped my fingers without shame around her collarbone and got hold of it. Her neck was warm.

Naturally, María Eugenia claimed I didn’t have hold of the chain, and Fatima and I maintained I had won fair and square, the three of us falling all over each other, tickling and slipping fingers around our mutual necks. The rest of the girls joined us in their own rough housing and loving embraces, until the nuns came to break it up and call us back into class. But María Eugenia and I had bonded for life.

Photo from Proctor Archives

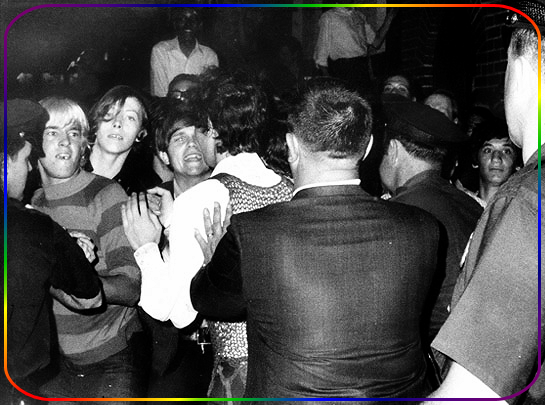

Nothing like this easy and inclusive intimacy awaited me at Alfred Plant, and I’m sure I didn’t help matters by being a late arrival into the school year, and South American. I could have been tall, blonde, and French, but I had to be difficult.

Andrea wasn’t the only girl who was afraid of getting too close to me, especially after the dogwood incident. There was also Cherry, who played field hockey and thought she might have seen promise in my short Chilean legs to make a good guard on the team. But later in the locker room she also saw that I didn’t shave my legs, and she was horrified. That was the end of my promising career in sports. Meanwhile, at home, nothing would make my mother change her mind about letting me near a razor or a depilatory cream, because she had a theory that this business of leg shaving was strictly an American subterfuge designed to get boys. No amount of my tears was going to make her understand I just wanted to be friends with Cherry.

If Cherry was the first to ditch me, the rest of the girls didn’t wait long. The Junior High experience was fiercely heterosexual. Everyone was dating or going steady with someone of the opposite sex, except for the absolute nerds and nobody bothered with them. I scanned the possibilities open to me and the panorama was bleak-- those boys were just plain ugly. Besides, dating before one’s eighteenth birthday was unheard of in my family and even then it would be with a chaperone. In our new country, there were no Latino role models for me of how to be a teenage girl. My only identification with stars and public figures was with American blacks who I understood were closer to Latinos, but even they were hardly ever on T.V. to show you how the dating game was done.

So I watched Star Trek for Nichele Nicholls, and I Spy for Bill Cosby, bought records by The Supremes and The Temptations, and held on to my crush on Paul. Inside though, I hadn’t changed. Gym class was torture and I was the only girl who still wore cross-your-heart double A’s and didn’t shave her legs.

I had never been confronted with such a bizarre custom as communal showers. It happened the first week I was enrolled at Alfred Plant, on a Thursday afternoon, the first day of our phys Ed class. By this time I could speak exactly ten words of English, and that included thank you and how do you do. After making us climb ropes which blistered my palms, and jump on a pummel horse which only tall girls could gracefully mount, the imposing Mrs. Eames sent us all to the showers.

There was a new word, showers, and soon I learned another one: embarrassed. Because this is what all the girls whispered in the locker room when they saw me retreat and put my school clothes back on in a hurry. Meanwhile, all the shameless Americans stripped naked and jumped into the wide-open shower, draping minuscule towels around their breasts when they came out. All my years of female bonding had not prepared me for this, and from that day until the end of the school year, I made sure never to break a sweat in gym class because there was no way I was going to take a shower in that place.

Over the summer it seemed as though life became more understandable, though I am still not entirely sure why. Part of it, I know, was due to being able to communicate. In my journal I began to write more enthusiastically about living in this new country, and my sentences were gradually shifting from Spanish into English, but I was still lost somewhere between teenage angst and plain loneliness. Understanding more of the language around me brought me closer to the youth culture, even if it was from a distance: I could hum some of the tunes I heard and my head floated in psychedelic sound, and when I discovered the ethic and the value of babysitting for our neighbors, my mother was finally persuaded to let me buy a pair of flared-leg jeans.

Photo from patterngate

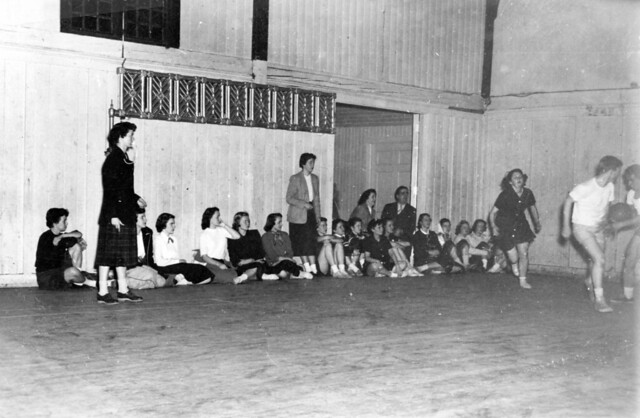

By the time Fall rolled around once more, our small family had witnessed the turning of the seasons in New England and moved away from the suburbs to a little semi-rural town in Eastern Connecticut, where the schools had no showers, the houses had no fences and the yards ended by a brook surrounded by blackberry bushes. In this town, half the neighborhood was African American or Polish, and there was even a Puerto Rican family down the street. Memories are hazy now, but I remember feeling wistfully happy, brave enough to abandon my memories of Chile, looking forward to the new school where perhaps I wouldn’t be so odd anymore.

And for a while, perhaps I wasn’t. In this school there were blue-eyed kids who came to homeroom smelling like a barn, because they had been up at dawn milking cows with their fathers. These boys got beat up by the football team before they got on the bus at the end of the day. The English teacher got pelted with spitballs as soon as he walked into the classroom because his hair was too long. I liked him right away. And there were two pregnant girls in my gym class; one of them, by the geometry teacher who was said to be a faggot because he wore different colored socks and penny loafers. I wasn’t sure what a faggot was, to tell the truth I had no idea, but I took this information in with equanimity.

By the second day of school, just about everyone had asked me where I was from and to say something in my language. The kids who hadn’t asked me were obviously not ever going to speak to me, so I figured it was better to have people talking to me than being ignored. I played the game. Some people thought my father was a diplomat, and others that we were fleeing political persecution. One girl asked if my mother was a singer, and another, if I was an orphan. It didn’t matter, it was what they wanted to hear, so I said yes, and embroidered the facts when I could. School wasn’t going to be so bad. And besides, finally, I found a friend.

Jackie, twice as tall as me, with bright red hair and brown eyes, lived on a farm, and since she was a girl, she didn’t have to milk the cows but her cousin, Jimmy, did. He already had a shiner on one eye by the second week.

The second week also signaled the advent of queer Thursday, a little known New England custom known to everyone but me which dictated that the entire student body should not wear green that day, unless they wanted to shout to the world that they were gay. I was wearing a lovely green pleated jumper my mother had made for me, with a fetching plaid blue and green shirt that had a little navy blue ribbon tie around the neck. I loved the little tie.

It didn’t take long for the whispers (she’s queer, she’s queer!) to register. I wasn’t sure what it meant, but I figured it had to do with me. There were some other unhappy souls caught wearing green that day, including Jimmy, who was wearing green overalls. Jackie despaired of what to do with the two of us, but to her credit, still consented to sit with us in the cafeteria at lunch. I played with my little tie. Looking around, I remember being aware that even though I could say most things in English, I still thought in Spanish.

Everyone was talking; the cafeteria was a strange, rowdy place. There were the two pregnant girls, having lunch with the football team. Most of the black kids were sitting at the same table, girls on one side, boys on the other. The English teacher was eating sloppy Joes with a fork, and had his nose stuck in a book. The principal was trying to fix his toupee. The farmer boys had double plates of food on their trays; the pretty girls laughed derisively as they passed by. At our table, Jackie was telling me I wasn’t really queer, it’s just that I was a foreigner and all.

And in Spanish I thought, no, this is true, I am queer. This is me.